Josephine Baker

Civil Rights Activist, Dancer, Singer (1906–1975)

Josephine Baker was a dancer and singer who became wildly popular in France during the 1920s. She also devoted much of her life to fighting racism.

Synopsis

Born Freda Josephine McDonald on June 3, 1906, in St. Louis, Missouri, Josephine Baker spent her youth in poverty before learning to dance and finding success on Broadway. In the 1920s she moved to France and soon became one of Europe's most popular and highest-paid performers. She worked for the French Resistance during World War II, and during the 1950s and '60s devoted herself to fighting segregation and racism in the United States. After beginning her comeback to the stage in 1973, Josephine Baker died of a cerebral hemorrhage on April 12, 1975, and was buried with military honors.

Early Life

Josephine Baker was born Freda Josephine McDonald on June 3, 1906, in St. Louis, Missouri. Her mother, Carrie McDonald, was a washerwoman who had given up her dreams of becoming a music-hall dancer. Her father, Eddie Carson, was a vaudeville drummer. He abandoned Carrie and Josephine shortly after her birth. Carrie remarried soon thereafter and would have several more children in the coming years.

To help support her growing family, at age 8 Josephine cleaned houses and babysat for wealthy white families, often being poorly treated. She briefly returned to school two years later before running away from home at age 13 and finding work as a waitress at a club. While working there, she married a man named Willie Wells, from whom she divorced only weeks later.

The Path to Paris

It was also around this time that Josephine first took up dancing, honing her skills both in clubs and in street performances, and by 1919 she was touring the United States with the Jones Family Band and the Dixie Steppers performing comedic skits. In 1921, Josephine married a man named Willie Baker, whose name she would keep for the rest of her life despite their divorce years later. In 1923, Baker landed a role in the musical Shuffle Alongas a member of the chorus, and the comic touch that she brought to the part made her popular with audiences. Looking to parlay these early successes, Baker moved to New York City and was soon performing in Chocolate Dandies and, along with Ethel Waters, in the floor show of the Plantation Club, where again she quickly became a crowd favorite.

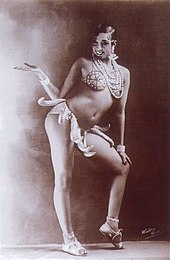

In 1925, at the peak of France’s obsession with American jazz and all things exotic, Baker traveled to Paris to perform in La Revue Nègre at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. She made an immediate impression on French audiences when, with dance partner Joe Alex, she performed the Danse Sauvage, in which she wore only a feather skirt.

However, it was the following year, at the Folies Bergère music hall, one of the most popular of the era, that Baker’s career would reach a major turning point. In a performance called La Folie du Jour, Baker danced wearing little more than a skirt made of 16 bananas. The show was wildly popular with Parisian audiences and Baker was soon among the most popular and highest-paid performers in Europe, having the admiration of cultural figures like Pablo Picasso, Ernest Hemingway and E. E. Cummings and earning herself nicknames like “Black Venus” and “Black Pearl.” She also received more than 1,000 marriage proposals.

Capitalizing on this success, Baker sang professionally for the first time in 1930, and several years later landed film roles as a singer in Zou-Zou andPrincesse Tam-Tam. The money she earned from her performances soon allowed her to purchase an estate in Castelnaud-Fayrac, in the southwest of France. She named the estate Les Milandes, and soon paid to move her family there from St. Louis.

Advertisement — Continue reading below

Racism and Resistance

In 1936, riding the wave of popularity she was enjoying in France, Baker returned to the United States to perform in the Ziegfield Follies, hoping to establish herself as a performer in her home country as well. However, she was met with a generally hostile, racist reaction and quickly returned to France, crestfallen at her mistreatment. Upon her return, Baker married French industrialist Jean Lion and obtained citizenship from the country that had embraced her as one of its own.

When World War II erupted later that year, Baker worked for the Red Cross during the occupation of France. As a member of the Free French forces she also entertained troops in both Africa and the Middle East. Perhaps most importantly, however, Baker did work for the French Resistance, at times smuggling messages hidden in her sheet music and even in her underwear. For these efforts, at the war’s end, Baker was awarded both the Croix de Guerre and the Legion of Honour with the rosette of the Resistance, two of France’s highest military honors.

Following the war, Baker spent most of her time at Les Milandes with her family. In 1947, she married French orchestra leader Jo Bouillon, and beginning in 1950 began to adopt babies from around the world. She adopted 12 children in all, creating what she referred to as her “rainbow tribe” and her “experiment in brotherhood.” She often invited people to the estate to see these children, to demonstrate that people of different races could in fact live together harmoniously.

Return to the U.S.

During the 1950s, Baker frequently returned to the United States to lend her support to the Civil Rights Movement, participating in demonstrations and boycotting segregated clubs and concert venues. In 1963, Baker participated, alongside Martin Luther King Jr., in the March on Washington, and was among the many notable speakers that day. In honor of her efforts, the NAACP eventually named May 20th “Josephine Baker Day.”

After decades of rejection by her countrymen and a lifetime spent dealing with racism, in 1973 Baker performed at Carnegie Hall in New York and was greeted with a standing ovation. She was so moved by her reception that she wept openly before her audience. The show was a huge success and marked Baker’s comeback to the stage.

Curtain Call

In April 1975, Josephine Baker performed at the Bobino Theater in Paris, in the first of a series of performances celebrating the 50th anniversary of her Paris debut. Numerous celebrities were in attendance, including Sophia Loren and Princess Grace of Monaco, who had been a dear friend to Baker for years. Just days later, on April 12, 1975, Baker died in her sleep of a cerebral hemorrhage. She was 69.

On the day of her funeral, more than 20,000 people lined the streets of Paris to witness the procession, and the French government honored her with a 21-gun salute, making Baker the first American woman in history to be buried in France with military honors.

______________________________________

Josephine Baker (3 June 1906 – 12 April 1975) was an American-born French dancer, singer, and actress who came to be known in various circles as the "Black Pearl," "Bronze Venus" and even the "Creole Goddess". Born Freda Josephine McDonald in St. Louis, Missouri, Josephine Baker became a citizen of France in 1937. She was fluent in both English and French.

Baker was the first black woman to star in a major motion picture, Zouzou (1934) or to become a world-famous entertainer. Baker refused to perform for segregated audiences in the United States and is noted for her contributions to the Civil Rights Movement. In 1968 she was offered unofficial leadership in the movement in the United States by Coretta Scott King, following Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination. Baker turned down the offer. She was also known for assisting the French Resistance during World War II,[3] and received the French military honor, the Croix de guerre and was made a Chevalier of the Légion d'honneur by General Charles de Gaulle.[4]

Contents

[hide]Early life[edit]

She was born as Freda Josephine McDonald in St. Louis, Missouri,[1][2] the daughter of Carrie McDonald. Her estate identifies vaudeville drummer Eddie Carson as her natural father; Carson abandoned Baker and her mother.[5]

Carrie and Eddie had a song-and-dance act, playing wherever they could get work. When Josephine was about a year old they began to carry her onstage occasionally during their finale.

Josephine was always poorly dressed and hungry, and she played in the railroad yards of Union Station. From this she developed her street smarts.[6]

When Baker was eight, she began working as a live-in domestic for white families in St. Louis.[7] One woman abused her, burning Baker's hands when the young girl put too much soap in the laundry.[8]

Career[edit]

Early years[edit]

Baker dropped out of school at the age of 13 and lived as a street child in the slums of St. Louis, sleeping in cardboard shelters and scavenging for food in garbage cans.[9]

Her street-corner dancing attracted attention, and she was recruited for the St. Louis Chorus vaudeville show at the age of 15. She headed to New York City during the Harlem Renaissance, performing at thePlantation Club and in the chorus of the groundbreaking and hugely successful Broadway revues Shuffle Along (1921) with Adelaide Hall[10] and The Chocolate Dandies (1924). She performed as the last dancer in achorus line. Traditionally the dancer in this position performed in a comic manner, as if she were unable to remember the dance, until the encore, at which point she would perform it not only correctly but with additional complexity. Baker was billed at the time as "the highest-paid chorus girl in vaudeville".[11][unreliable source?]

Paris and rise to fame[edit]

Baker sailed to Paris, France, for a new venture, and opened in "La Revue Nègre" on 2 October 1925, at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées.[5][12] In Paris, she became an instant success for her erotic dancing, and for appearing practically nude on stage. After a successful tour of Europe, she broke her contract and returned to France to star at the Folies Bergère, setting the standard for her future acts.

Baker performed the 'Danse sauvage,' wearing a costume consisting of a skirt made of a string of artificial bananas. Her success coincided (1925) with the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs, which gave birth to the term "Art Deco", and also with a renewal of interest in non-western forms of art, including African. Baker represented one aspect of this fashion. In later shows in Paris, she was often accompanied on stage by her pet cheetah, Chiquita, who was adorned with a diamond collar. The cheetah frequently escaped into the orchestra pit, where it terrorized the musicians, adding another element of excitement to the show.[11][unreliable source?]

After a short while, Baker was the most successful American entertainer working in France. Ernest Hemingway called her "the most sensational woman anyone ever saw."[13][14]

In addition to being a musical star, Baker also starred in three films which found success only in Europe: the silent film Siren of the Tropics (1927), Zouzou (1934) andPrincesse Tam Tam (1935). She also starred in Fausse Alerte in 1940.[15]

At this time she also scored her most successful song, "J'ai deux amours" (1931). She became a muse for contemporary authors, painters, designers and sculptors, includingLangston Hughes, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Pablo Picasso, and Christian Dior.

Under the management of Giuseppe Pepito Abatino, a Sicilian former stonemason who passed himself off as a count, Baker's stage and public persona, as well as her singing voice, were transformed. In 1934, she took the lead in a revival of Jacques Offenbach's opera La créole, which premiered in December of that year for a six-month run at the Théâtre Marigny on the Champs-Élysées of Paris. In preparation for her performances, she went through months of training with a vocal coach. In the words of Shirley Bassey, who has cited Baker as her primary influence, "... she went from a 'petite danseuse sauvage' with a decent voice to 'la grande diva magnifique'... I swear in all my life I have never seen, and probably never shall see again, such a spectacular singer and performer."[16]

Despite her popularity in France, Baker never attained the equivalent reputation in America. Upon a visit to the United States in 1935–36, she was met with lukewarm audiences. Her star turn in the Ziegfeld Follies generated less than impressive box office numbers, and she was replaced by Gypsy Rose Lee later in the run.[17] Timemagazine referred to her as a "Negro wench".[18] She returned to Europe heartbroken.[5]

Baker returned to Paris in 1937, married a Jewish Frenchman, Jean Lion, and became a French citizen.[19] They were married in the French town of Crèvecœur-le-Grand. The wedding was presided over by mayor Jammy Schmidt.

Work during World War II[edit]

In September 1939, when France declared war on Germany in response to the invasion of Poland, Baker was recruited by Deuxième Bureau, French military intelligence, as an "honorable correspondent". Baker collected what information she could about German troop locations from officials she met at parties. She specialized in gatherings at embassies and ministries, charming people as she had always done, while gathering information. Her café-society fame enabled her to rub shoulders with those in the know, from high-ranking Japanese officials to Italian bureaucrats, and to report back what she heard. She attended parties at the Italian embassy without raising suspicions and gathered information.[20]:182–269

When the Germans invaded France, Baker left Paris and went to the Château des Milandes, her home in the south of France. She housed friends who were eager to help the Free French effort led by Charles de Gaulle and supplied them with visas.[21] As an entertainer, Baker had an excuse for moving around Europe, visiting neutral nations such as Portugal, as well as some in South America. She carried information for transmission to England, about airfields, harbors, and German troop concentrations in the West of France. Notes were written in invisible ink on Josephine's sheet music.[20]:232–269

Later in 1941, she and her entourage went to the French colonies in North Africa. The stated reason was Baker's health (since she was recovering from another case of pneumonia) but the real reason was to continue helping the Resistance. From a base in Morocco, she made tours of Spain. She pinned notes with the information she gathered inside her underwear (counting on her celebrity to avoid a strip search). She befriended the Pasha of Marrakesh, whose support helped her through a miscarriage (the last of several). After the miscarriage, she developed an infection so severe it required a hysterectomy. The infection spread and she developed peritonitis and then septicemia. After her recovery (which she continued to fall in and out of), she started touring to entertain British, French, and American soldiers in North Africa. The Free French had no organized entertainment network for their troops, so Baker and her friends managed for the most part on their own. They allowed no civilians and charged no admission. To this day, veterans greatly remember her performances.[20]

In Cairo, Egypt's King Farouk asked her to sing; she refused because Egypt had not recognized Free France and remained neutral. However, she offered to sing in Cairo at a celebration of honor for the ties between Free France and Egypt, and asked Farouk to preside, a subtle indication of which side his officially neutral country leaned toward.[22]

After the war, Baker received the Croix de guerre and the Rosette de la Résistance. She was made a Chevalier of the Légion d'honneur by General Charles de Gaulle.[23]

Later career[edit]

In 1949, a reinvented Baker returned in triumph to the Folies Bergere. Bolstered by recognition of her wartime heroics, Baker the performer assumed a new gravitas, unafraid to take on serious music or subject matter. The engagement was a rousing success, and reestablished Baker as one of Paris' preeminent entertainers.

In 1951 Baker was invited back to the US for a nightclub engagement in Miami. After winning a public battle over desegregating the club's audience, Baker followed up her sold-out run at the club with a national tour. Rave reviews and enthusiastic audiences accompanied her everywhere, climaxed by a parade in front of 100,000 people in Harlem in honor of her new title: NAACP's "Woman of the Year." Her future looked bright, with six months of bookings and promises of many more to come.

An incident at the Stork Club interrupted and overturned her plans. Baker criticized the club's unwritten policy of discouraging black patrons, then scolded columnist Walter Winchell, an old ally, for not rising to her defense. Winchell responded swiftly with a series of harsh public rebukes, including accusations of Communist sympathies (a serious charge at the time). The ensuing publicity resulted in the termination of Baker's work visa, forcing her to cancel all her engagements and return to France. It was almost a decade before US officials allowed her back into the country.[24]

In January 1966, Fidel Castro invited Baker to perform at the Teatro Musical de La Habana in Havana, Cuba at the 7th anniversary celebrations of his revolution. Her spectacular show in April broke attendance records. In 1968, Baker visited Yugoslavia and made appearances in Belgrade and in Skopje.

In her later career, Baker faced financial troubles. She commented, "Nobody wants me, they've forgotten me"; but family members encouraged her to continue performing. In 1973 she performed at Carnegie Hall to a standing ovation. In 1974 she appeared in a Royal Variety Performance at the London Palladium, and then at the Monacan Red Cross Gala, celebrating her 50 years in French show business. Advancing years and exhaustion began to take their toll; she sometimes had trouble remembering lyrics, and her speeches between songs tended to ramble. She still continued to captivate audiences of all ages.[20]

Civil rights activism[edit]

Although based in France, Baker supported the American Civil Rights Movement during the 1950s. When she arrived in New York with her husband Jo, they were refused reservations at 36 hotels because she was black. She was so upset by this treatment that she wrote articles about the segregation in the United States. She also began traveling into the South. She gave a talk at Fisk University, a historically black college in Nashville, Tennessee, her subject being "France, North Africa And The Equality Of The Races In France".[20]

She refused to perform for segregated audiences in the United States, although she was offered $10,000 by a Miami club.[3] (The club eventually met her demands). Her insistence on mixed audiences helped to integrate live entertainment shows in Las Vegas, Nevada, then one of the most segregated cities in America.[11][unreliable source?] After this incident, she began receiving threatening phone calls from people claiming to be from the Ku Klux Klan but said publicly that she was not afraid of them.[20]

In 1951, Baker made charges of racism against Sherman Billingsley's Stork Club in Manhattan, where she alleged that she had been refused service.[25][26] Actress Grace Kelly, who was at the club at the time, rushed over to Baker, took her by the arm and stormed out with her entire party, vowing never to return (although she returned on 3 January 1956 with Prince Rainier of Monaco). The two women became close friends after the incident.[27]

When Baker was near bankruptcy, Kelly offered her a villa and financial assistance (Kelly by then was princess consort of Rainier III of Monaco). (However, during his work on the Stork Club book, author and New York Times reporter Ralph Blumenthal was contacted by Jean-Claude Baker, one of Josephine Baker's sons. Having read a Blumenthal-written story about Leonard Bernstein's FBI file, he indicated that he had read his mother's FBI file and, using comparison of the file to the tapes, said he thought the Stork Club incident was overblown.[28])

Baker worked with the NAACP.[3] Her reputation as a crusader grew to such an extent that the NAACP had Sunday 20 May 1951 declared Josephine Baker Day. She was presented with life membership of the NAACP by Nobel Peace Prize winner Dr. Ralph Bunche. The honor she was paid spurred her to further her crusading efforts with the "Save Willie McGee" rally after he was convicted of the 1948 beating death of a furniture shop owner in Trenton, New Jersey. As Josephine became increasingly regarded as controversial, many blacks began to shun her, fearing that her reputation would hurt their cause.[20]

In 1963, she spoke at the March on Washington at the side of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.[29] Baker was the only official female speaker. While wearing her Free French uniform emblazoned with her medal of the Légion d'honneur, she introduced the "Negro Women for Civil Rights."[30] Rosa Parks and Daisy Bates were among those she acknowledged, and both gave brief speeches.[31]

After King's assassination, his widow Coretta Scott King approached Baker in the Netherlands to ask if she would take her husband's place as leader of the American Civil Rights Movement. After many days of thinking it over, Baker declined, saying her children were "too young to lose their mother".[31]

Personal life[edit]

Relationships[edit]

Baker was married four times. Her first marriage was to American Pullman porter Willie Wells when she was 13 years old. The marriage was reportedly very unhappy and the couple divorced a short time later. Another short-lived marriage followed to Willie Baker in 1921; she retained Baker's last name because her career began taking off during that time, and it was the name by which she became best known. In 1925 she began an extramarital relationship with the Belgian novelist Georges Simenon.[32]

In 1937 Baker married Frenchman Jean Lion. She became a French citizen and became a permanent expatriate. She and Lion separated before he died.

She married French composer and conductor Jo Bouillon in 1947, but their union also ended in divorce. She was later involved for a time with the artist Robert Brady, but they never married.[33][34] Her adopted son Jean-Claude Baker describes his mother as a bisexual, having had relationships with men and women.[35] In her later years, Baker converted to Roman Catholicism.[36]

Children[edit]

During Baker's work with the Civil Rights Movement, she began adopting children, forming a family she often referred to as "The Rainbow Tribe". Josephine wanted to prove that "children of different ethnicities and religions could still be brothers." She often took the children with her cross-country, and when they were chez Château des Milandes, she arranged tours so visitors could walk the grounds and see how natural and happy the children in "The Rainbow Tribe" were.[37] Baker raised two daughters, French-born Marianne and Moroccan-born Stellina, and ten sons, Korean-born Jeannot (or Janot), Japanese-born Akio, Colombian-born Luis, Finnish-born Jari (now Jarry), French-born Jean-Claude and Noël, Israeli-born Moïse, Algerian-born Brahim, Ivorian-born Koffi, and Venezuelan-born Mara.[38][39] For some time, Baker lived with her children and an enormous staff in a castle, Château des Milandes, in Dordogne, France, with her fourth husband, Jo Bouillon.

Later years and death[edit]

In 1964, Josephine Baker lost her castle due to unpaid debts; after, Princess Grace offered her an apartment in Roquebrune, near Monaco.[citation needed]

Baker was back on stage at the Olympia in Paris in 1968, in Belgrade in 1973, at Carnegie Hall in 1973, at the Royal Variety Performance at the London Palladium in 1974, and at the Gala du Cirque in Paris in 1974. On 8 April 1975, Baker starred in a retrospective revue at the Bobino in Paris, Joséphine à Bobino 1975, celebrating her 50 years in show business. The revue, financed notably by Prince Rainier, Princess Grace, and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, opened to rave reviews. Demand for seating was such that fold-out chairs had to be added to accommodate spectators. The opening night audience included Sophia Loren, Mick Jagger, Shirley Bassey, Diana Ross, and Liza Minnelli.[40]

Four days later, Baker was found lying peacefully in her bed surrounded by newspapers with glowing reviews of her performance. She was in a coma after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage. She was taken to Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, where she died, aged 68, on 12 April 1975.[40][41] She received a full Roman Catholic[42] funeral which was held at L'Église de la Madeleine.[43][44] The only American-born woman to receive full French military honors at her funeral, Baker's funeral was the occasion of a huge procession. After a family service at Saint-Charles Church in Monte Carlo,[45] Baker was interred at Monaco's Cimetière de Monaco.[40]

Legacy[edit]

Place Joséphine Baker in the Montparnasse Quarter of Paris was named in her honor. She has also been inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame,[46] and on 29 March 1995, into the Hall of Famous Missourians.[47] The Piscine Joséphine Baker is a swimming pool along the banks of the Seine in Paris named for her.

Writing in the on-line BBC magazine in late 2014, Darren Royston, historical dance teacher at RADA credited Baker with being the Beyonce of her day, and bringing the Charleston to Britain.[48]

Two of Baker's sons, Jean-Claude and Jarry (Jari), grew up to go into business together, running the restaurant Chez Josephine on Theatre Row, 42nd Street, New York. It celebrates Baker's life and works.[49]

Château des Milandes, a castle near Sarlat in the Dordogne, was Josephine Baker's home where she raised her twelve children. It is open to the public and displays her stage outfits including her banana skirt (of which there are apparently several). It also displays many family photographs and documents as well as her Legion of Honour medal. Most rooms are open for the public to walk through including bedrooms with the cots where her children slept, a huge kitchen, and a dining room where she often entertained large groups. The bathrooms were designed in art deco style but most rooms retained the French chateau style.

Portrayals[edit]

- In 2006, Jérôme Savary produced a musical, A La Recherche de Josephine – New Orleans for Ever (Looking for Josephine). The story revolved around the history of jazz and Baker's career.[50][51]

- In 1991, Baker's life story, The Josephine Baker Story, was broadcast on HBO. Lynn Whitfield portrayed Baker, and won an Emmy Award forOutstanding Lead Actress in a Miniseries or a Special—becoming the first Black actress to win the award in this category.[52]

- In 2002, played by Karine Plantadit in Frida.[53][54]

- Josephine Baker appears in her role as a member of the French Resistance in Johannes Mario Simmel's 1960 novel, Es Muss Nicht Immer Kaviar Sein (C'est pas toujours du caviar).[55]

- The 2004 erotic novel Scandalous by British author Angela Campion uses Baker as its heroine and is inspired by Baker's sexual exploits and later adventures in the French Resistance. In the novel, Baker, working with a fictional black Canadian lover named Drummer Thompson, foils a plot by French fascists in 1936 Paris.[56]

- Her influence upon and assistance with the careers of husband and wife dancers Carmen De Lavallade and Geoffrey Holder are discussed and illustrated in rare footage in the 2005 Linda Atkinson/Nick Doob documentary, Carmen and Geoffrey.[57][58]

- Diana Ross famously portrayed Josephine Baker in both her Tony Award-winning Broadway and television show An Evening with Diana Ross. When the show was made into an NBC television special entitled The Big Event: An Evening with Diana Ross, Ross further embellished her role as Josephine. She worked for years to make a feature film of her life; to no avail. Diana considers it a "lost dream".[59]

- In 1986, Helen Gelzer[60] portrayed Josephine on the London stage for a limited run in the musical Josephine - ‘a musical version of the life and times of Josephine Baker’ with book, lyrics and music by Michael Wild.[61] The show was produced by Josephine Baker’s longtime friend Jack Hocket in conjunction with Premier Box-Office and the musical director was Paul Maguire. Gelzer also recorded a studio cast album titled, "Josephine".

- The italo-belge francophone singer composer Salvatore Adamo pays tribute to Josephine Baker with the song "Noël Sur Les Milandes" (album: Petit Bonheur – EMI 1970).

- Beyoncé Knowles has portrayed Baker on various accounts throughout her career. During the 2006 Fashion Rocks show, Knowles performed "Dejá Vu" in a revised version of the Danse banane costume. In Knowles's video for "Naughty Girl", she is seen dancing in a huge champagne glass à La Baker. In I Am... Yours: An Intimate Performance at Wynn Las Vegas, Beyonce lists Baker as an influence of a section of her live show.[62]

- In the 1997 animated film Anastasia, Baker appears with her cheetah during the musical number "Paris Holds the Key (to Your Heart)".[63][64]

- A character clearly based on Baker (topless, wearing the famous "banana skirt") appears in the opening sequence of the 2003 animated film Les Triplettes de Belleville.[65]

- A character loosely based on Baker is featured in an episode of Hogan's Heroes titled, "Is General Hammerschlag Burning?", which originally aired on 18 November 1967. The character, Kumasa (played byBarbara McNair), is a chanteuse based in Paris. She later reveals herself to be Carol Dukes, a high school classmate of Sergeant James Kinchloe (Ivan Dixon), on whom she had a secret crush.

- A German submariner mimics Baker's Danse banane in the film Das Boot.[66]

- In 2010, Keri Hilson portrayed Baker in her single "Pretty Girl Rock".[67]

- Artist Hassan Musa depicted Baker in a series of paintings called Who needs Bananas?[68]

- In 2011, Sonia Rolland portrayed Baker in the film Midnight in Paris.[69][70]

- Josephine Baker was heavily featured in the 2012 book Josephine's Incredible Shoe & The Blackpearls by Peggi Eve Anderson-Randolph.[71]

- In July 2012, Cheryl Howard opened in The Sensational Josephine Baker, written and performed by Howard and directed by Ian Streicher at the Beckett Theatre of Theatre Row on 42nd Street in New York City, just a few doors down from the restaurant "Chez Josephine", run by two of her children.[72][73]

- In July 2013, Cush Jumbo's debut play Josephine and I premieres at the Bush Theatre,London[74] It was re-produced in New York City at The Public Theater's Joe's Pub from 27 February to 5 April 2015. <http://www.publictheater.org/en/Public-Theater-Season/Josephine-and-I/>

Film credits[edit]

- La Sirène des tropiques (1927)[75]

- Le pompier des Folies Bergères (1928), short subject

- Zouzou (1934)[15]

- Princesse Tam Tam (1935)[15]

- Fausse alerte (1940)[76]

- Moulin Rouge (1941)[15]

- An jedem Finger zehn (1954)[15]

- Carosello del varietà (1955)[15]

_____________________________________________________________________________

Josephine Baker, original name Freda Josephine McDonald (born June 3, 1906, St. Louis, Mo., U.S.—died April 12, 1975, Paris, France), American-born French dancer and singer who symbolized the beauty and vitality of black American culture, which took Paris by storm in the 1920s.

Baker grew up fatherless and in poverty. Between the ages of 8 and 10 she was out of school, helping to support her family. As a child Baker developed a taste for the flamboyant that was later to make her famous. As an adolescent she became a dancer, touring at 16 with a dance troupe from Philadelphia. In 1923 she joined the chorus in a road company performing the musical comedyShuffle Along and then moved to New York City, where she advanced steadily through the show Chocolate Dandies on Broadway and the floor show of the Plantation Club.

In 1925 she went to Paris to dance at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in La Revue Nègre and introduced her danse sauvage to France. She went on to become one of the most popular music-hall entertainers in France and achieved star billing at the Folies-Bergère, where she created a sensation by dancing seminude in a G-string ornamented with bananas. She became a French citizen in 1937. She sang professionally for the first time in 1930, made her screen debut as a singer four years later, and made several more films before World War II curtailed her career.

During the German occupation of France, Baker worked with the Red Cross and the Résistance, and as a member of the Free French forces she entertained troops in Africa and the Middle East. She was later awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Legion of Honour with the rosette of the Résistance. After the war much of her energy was devoted to Les Milandes, her estate in southwestern France, from which she began in 1950 to adopt babies of all nationalities in the cause of what she defined as “an experiment in brotherhood” and her “rainbow tribe.” She retired from the stage in 1956, but to maintain Les Milandes she was later obliged to return, starring in Paris in 1959. She traveled several times to the United States to participate in civil rights demonstrations. In 1968 her estate was sold to satisfy accumulated debt. She continued to perform occasionally until her death in 1975, during the celebration of the 50th anniversary of her Paris debut.

_____________________________________________________________________

Josephine Baker, original name Freda Josephine McDonald (b. June 3, 1906, St. Louis, Missouri — d. April 12, 1975, Paris, France) was an American-born French dancer and singer who symbolized the beauty and vitality of black American culture, which took Paris by storm in the 1920s.

Baker grew up fatherless and in poverty. Between the ages of 8 and 10 she was out of school, helping to support her family. As a child, Baker developed a taste for the flamboyant that was later to make her famous. As an adolescent, she became a dancer, touring at 16 with a dance troupe from Philadelphia. In 1923 she joined the chorus in a road company performing the musical comedy Shuffle Along and then moved to New York City, where she advanced steadily through the show Chocolate Dandies on Broadway and the floor show of the Plantation Club.

In 1925 she went to Paris to dance at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in La Revue Nègre and introduced her danse sauvage to France. She went on to become one of the most popular music-hall entertainers in France and achieved star billing at the Folies-Bergere, where she created a sensation by dancing semi-nude in a G-string ornamented with bananas. She became a French citizen in 1937. She sang professionally for the first time in 1930, made her screen debut as a singer four years later, and made several more films before World War II curtailed her career.

During the German occupation of France, Baker worked with the Red Cross and the Resistance, and as a member of the Free French forces she entertained troops in Africa and the Middle East. She was later awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Legion of Honour. with the rosette of the Résistance. After the war much of her energy was devoted to Les Milandes, her estate in southwestern France, from which she began in 1950 to adopt babies of all nationalities in the cause of what she defined as “an experiment in brotherhood” and her “rainbow tribe.” She retired from the stage in 1956, but to maintain Les Milandes she was later obliged to return, starring in Paris in 1959. She traveled several times to the United States to participate in civil rights demonstrations. In 1968 her estate was sold to satisfy accumulated debt. She continued to perform occasionally until her death in 1975, during the celebration of the 50th anniversary of her Paris debut.

No comments:

Post a Comment